How To Think Like A Historian

An interactive experience that explores research presented on Interracial Intimacies: Sex and Race in Toronto 1910 to 1950.

How To Think Like A HistorianAn interactive experience that explores research presented on Interracial Intimacies: Sex and Race in Toronto 1910 to 1950. |

|

|

|

Meet Elise Chenier Listen to Elise Chenier introduce her research and how this research took form. |

|

|

Master's Thesis Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, 1993-1995 Research on Lesbian Bar Culture in Toronto in the 1950s and 60s. |

|

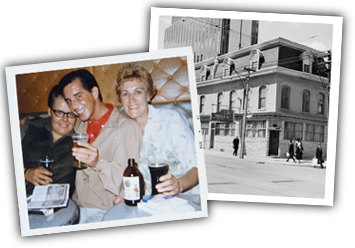

Photo: Dorothy Fairbairn and friends having a drink and a laugh at the Continental Hotel, n.d. [early 1960s?]

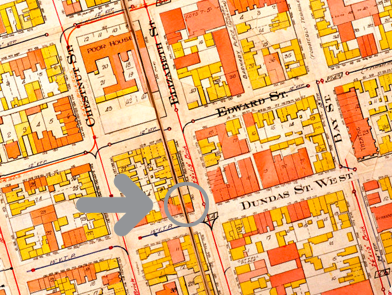

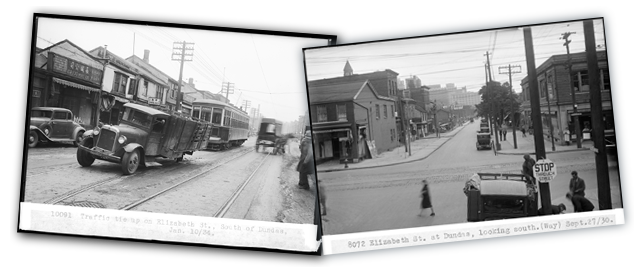

From the mid-1950s to the late 1960s, lesbian’s main hang-out was a beer parlour in the centre of Chinatown. At the corner of Elizabeth Street and Dundas Street West. |

|

Method Newspapers are not as reliable as you might think. Reporters can get facts wrong, and news reporting is always biased. For example, choosing what is news and what isn’t reflects a bias. The tabloids, which were also known as “scandal sheets” because they focused on and even created scandals, and “the yellow press” because they were printed on a cheaper quality paper that was actually yellow, are even more problematic. How then should historians use the tabloid newspapers? There are two principle ways: 1. they can be read to reveal the biases of the time among the sector of the population who produced and read tabloid newspapers, and 2. we can “read against the grain.” The second method is common among social historians who have to rely on sources that are deeply biased to learn about the past. Some of the stories in the tabloids were so sensational that I wondered if they were actually fiction. Could I “read against the grain,” which means trying to find out something about the lived experiences of the people who appear in overwhelmingly anti-homosexual, sexist, and racist news accounts? Two of the women who I interviewed for my Master’s thesis appeared in the tabloids, indicating to me that the stories were based on at least some truth. In one case Ivy Barber, whose street name was Lynn Winters, was about to be released from prison (she was incarcerated for drug use) and a gossip columnist noted this in the paper, which often reported on the goings-on among the women who frequented the Continental Hotel’s beer parlour, the centre of Toronto’s public lesbian culture. Many women enjoyed reading about themselves in the tabloids.

It Begins With Discovery While researching I discovered an interesting connection between lesbians, sex workers, and men of Chinese heritage. |

|

Getting Started On A Research Project |

|

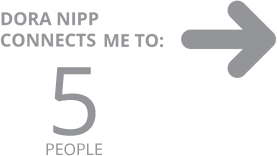

Method When beginning a research project, we seek out the experts. Usually this means reading the work of other historians on your chosen subject. If you want to interview people and you don't have personal connections you can draw upon, you do the same thing. You go to the experts, which in this case can mean scholars, activists, or community leaders. Oral historians develop skills in finding people in the community and building relationships of trust. Talk To Experts Dora Nipp is a well-known historian, lawyer, ethnologist, and activist who I contacted in the hope that she could suggest some community members I could interview. She very kindly put me in touch with a number of people, all of who agreed to be interviewed. |

|

Garfield Chan describes the presence of lesbians and sex workers at Sai Woo, the Chinese restaurant where he worked.

|

|

Tom Lock, Chinatown Pharmacist, as told by his son, filmmaker Keith Lock.

First rule of interviewing is to check all of your equipment in advance. I interviewed Keith Lock on the phone. Phone interviews are not ideal but sometimes they are the only option. Our interview took place in my pre-iPhone days when recording a telephone conversation required special equipment. I did not have such equipment but I did have a small digital voice recorder. My solution was to simply hold it up to the phone and record our conversation. Of course, I had Lock’s permission to make a recording. Getting an interviewee’s permission to record a conversation is ethically responsible and required by my university’s Research Ethics Board. To be honest, I was not as familiar with the recorder as I should have been. I had used it successfully before but for whatever reason when the phone conversation ended there was no recording. Either the equipment failed, or I did. Fortunately for me Lock did an interview with the Multicultural History Society of Ontario (MHSO) and discussed many of the same events that he discussed with me. What you see here is the MHSO interview, not mine. The interview is posted here with the permission of the MHSO. Now, I always record interviews to two separate devices: a video camera and a free program called Audacity which is on my laptop. In a pinch I’ll use my iPhone, which I find makes excellent quality voice recordings. There are two lessons here: equipment can fail so try to have a back-up, and practice using your equipment before your interview to reduce the possibility of errors. Alfie Yip Interview

|

|

Mah describes how she came to write the first historical study of Toronto's Chinese community.

Valerie Mah Undergraduate research essays.

|

|

Hired Research Assistant: Bradley Lee Wondering if it might not be better to hire an Asian male to get this next story, I hired journalist and researcher Bradley Lee to conduct interviews for me. After completing three, he decided that the project did not really speak to his interests and suggested I hire Kenneth Huynh. |

Hired Research Assistant: Kenneth Huyhn Kenneth Huynh, a PhD candidate at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, conducts interviews over the course of a year. |

Method This is the first time I have hired anyone to do my interviews for me. I did it for two reasons: I thought interviewees might be more open with another Asian man than they would be with me, a white woman; and I now live in Vancouver, BC, a very long way from Toronto. They both did a great job, but I discovered that I much prefer to conduct interviews myself. For me, oral history is never just about the topic. I like to get a sense of the person I am interviewing as well as their experience; I like to let them tell me a little bit about what they want to tell me before probing around my topic. This is part of the trust-building process, and is especially important when exploring topics usually considered very private, such as sexuality. I also like to allow myself to be surprised by what I learn. As you will see, this project ended up being about a surprise, and not what I had originally set out to study.

|

Steve Young describes the difficult circumstances under which many men of Chinese heritage lived.

|

|

Ed Wong recounts the sex trade in Chinatown

Ed Wong Adoption Story

|

|

Alice Yeh Interview

Alice Yeh On Discrimation in Victoria and Toronto Compared

Alan Joe On Discrimation in Victoria and Toronto Compared

|

|

Dora Nipp Emails me to let me know that Arlene Chan has a new book coming out about Toronto's Chinatown. |

|

Arlene Chan The thing about oral history is you never really know what you are going to find out. What I learned from Mavis I discovered only by being open to hearing about something outside my chosen time frame. The information she provided was so historically significant [see the video just to the right of this item] that I set aside my proposed project on the relationship between sex workers, lesbians, and men of Chinese heritage in the 1950s and 60s and decided to explore intimate relationships between men of Chinese heritage and non-Asian women between 1910 and 1950. Being very familiar with Canadian historiography, I knew that this topic would make a greater contribution to the literature than the one I had chosen. It also interested me a great deal. |

|

Method As you can see by clicking on the transcript, my conversation with Mavis began like this: Elise: Okay. Well, first I want to thank you so much for agreeing to see me. Mavis: Well, I wasn't sure what it was all about. Arlene [Chan] said you were doing research on the'50s and '60s. Too bad you weren't doing it, well, the '40s and '50s. There were two ways I could respond: I could confirm my interest in the 50s and 60s, or, I could ask her what she thought it was important about the 1940s. What I actually said was a combination of both: Elise: Oh yeah. No, I'm including the 40s too, so... Well, I was as of that very moment. I wanted to find out what she had to tell me. The thing about oral history is you never really know what you are going to find out. What I found out from Mavis, and I only found this out by being flexible and open to hearing about something outside of my chosen time frame, was so significant that I changed the focus of my research [see the video just to the right of this item]. I set aside my proposed project on the relationship between sex workers, lesbians and men of Chinese heritage in the 1950s and 60s and decided to examine intimate relationships between men of Chinese heritage and non-Asian women. As someone who is very familiar with Canadian historiography, I knew that this topic would make a greater contribution to the literature than the one I had chosen. It also interested me a great deal. There are other, equally legitimate reasons to change topics. You find something that interests you more, or you are having too much difficulty finding good sources for your initial topic. In my opinion, the very best reason to take on a topic is because it interests you, but keep in mind that you always have to make a case for a topic’s historical significance. In the early stages of your research let your curiosity roam freely. This applies to every type of source you encounter: magazines and newspapers, films, novels, government documents, military records, photographic collections, letters and diaries, recipe books, and so on. |

Method Oftentimes when narrators (the term I use for the people I interview) read a transcript of our interview they are surprised and embarrassed by how inarticulate they come across. We see how much we say “uh” and “ah” (not everyone transcribes ums and ahs, but I do). Sentences are not always finished, and we often bounce from one story to another because that’s how our memory typically works. When historians work with written documents, we quote from them exactly as the text appears. However, what should we do if narrators don’t like the way they sound? Mavis asked to edit her transcript so that sentences were complete, her points and information was clearer, and the ums and ahs were excised. It was the edited transcript that is posted here, and that I quote from in the article. My reasoning was this: I edit my own writing for clarity, why shouldn’t I allow her to do the same? Also, the point of quoting directly from our sources is to be accurate. Mavis’ edits did not change the accuracy of the story. This is a more collaborative approach to using oral testimony, one that empowers the narrator to tell their story as they want it told, and to be represented in a way that is respectful and dignified. A Significant Discovery The thing about oral history is you never really know what you are going to find out. What I learned from Mavis I discovered only by being open to hearing about something outside my chosen time frame. The information she provided was so historically significant [see the video just to the right of this item] that I set aside my proposed project on the relationship between sex workers, lesbians, and men of Chinese heritage in the 1950s and 60s and decided to explore intimate relationships between men of Chinese heritage and non-Asian women between 1910 and 1950. Being very familiar with Canadian historiography, I knew that this topic would make a greater contribution to the literature than the one I had chosen. It also interested me a great deal. |

|

|

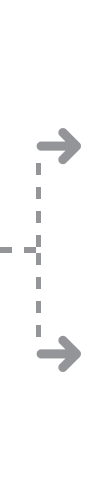

Are photographs reliable sources? Have a look at these websites for interesting examples of doctored photographs. Digital Doctoring: can we trust photographs? The early history of faking war on film Why might a family photograph be doctored? Is there any evidence that any of these photos have been doctored? How has digital technology changed the way historians authenticate photographs? Please note that in the photograph in which a face has been blurred, the ‘doctoring’ was done at Mavis’ request. She was concerned that the descendants of the man in the photo might recognize him, and that the image would have negative repercussions for the family. Method Mavis shows me her family album. Mavis would turn out to be an ongoing collaborator on this project, but at this stage I had no idea if this would be our only meeting, so I wanted to make sure I captured everything. For this reason, I recorded Mavis going through her album to ensure that I could reference the photos to her description of them. It would have been harder to make sense of the information she gave me if I had not captured video footage the photos as she talked about them.

Video: Mavis Reflects On Her Family Album Realising that this album was very special, I recorded Mavis going through it to ensure that the information she gave me about the photos, and the photos themselves were part of the historical record I was gathering. After all, who knew if I would ever see her or these photos again. |

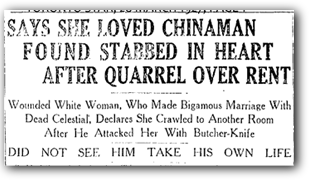

Question What picture of men of Chinese heritage do the tabloids paint? What impact would this have on men of Chinese heritage? On non-Asian Torontonians? If someone wanted to challenge this image, how could they have done so? Question Like many newspapers, Toronto’s tabloids have not been digitized. The only existing copies are archived in the Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library‘s James Baldwin Room. As you may be able to tell from the images, these newspapers are bound in large volumes. The images you see here are photographs taken of the original page. Unfortunately some of the photos are blurry, and sometimes the binding made it hard to capture the date. The darkness of the pages is only partly due to the age of the paper. The "scandal sheets" or "tabloids" were also referred to as the "yellow press" because newspapers of this type were published on cheap, yellow paper. Students today are accustomed to doing most of their research online, but historical research almost always requires visiting archives and libraries where primary sources are stored. For most of us, archival work is the most tedious and the most exciting part of what we do. You can spend days in an archives without finding a single item of interest, and then suddenly you strike gold. Another aspect of archival research that I and many of my students enjoy is the sensation of touching the past when you hold in your hands a document or object once held by someone living in the era you are studying. For some reason, this seems to bring the past alive more than a book or even a documentary can.

The Scandalous Tabloids In my research I discovered that Toronto’s tabloid newspapers were an interesting source of articles on people on Chinese heritage, white women with Chinese men and about sex workers.

Some of these images may be difficult to read. Click on Method to find out why. |

|

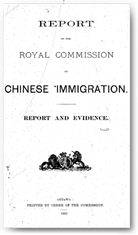

Question Most of the testimony the Commission heard was provided by people living in British Columbia in 1885. Can the Commission’s Report be used as a source to write about Toronto between 1910-1950? If so, why, and what issues must the historian take into consideration when doing so? If not, why not? Provide your answer in one paragraph. Royal Commission I read the 1885 Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration and find Edith Wharton’s testimony particularly intriguing. It shows that at least some white women disputed white people’s characterization of men of Chinese heritage as untrustworthy, dangerous, and a threat to white women’s “honour.”

|

|

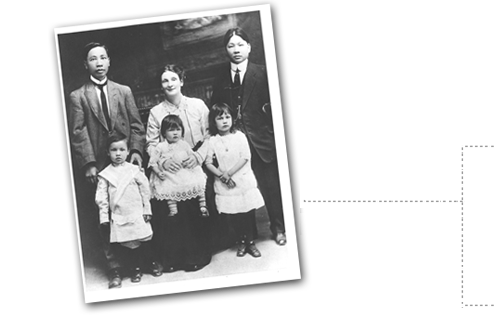

Alice Grady and Kwan Sue In 1911 20-year-old Irish immigrant Alice Grady married 27-year-old restaurateur Kwan Sue. By 1919 they had five children. Frank was the fourth born and does not appear in this photo. Shortly after Alice had Frank she and the children moved with Sue from Toronto to Guangdong province, Sue’s place of birth. Alice and the children -- including a fifth born in China -- remained in Guangdong, but Kwan would return to Toronto, open a new restaurant, work for a few years, sell it, and return home. He did this repeatedly, though how often is not known. It appears to have been a very successful strategy: he built a large dailou (pillbox home, see photos) in Fuheli Village where many of his family members also lived. Sadly Alice died in 1921 of unknown causes, possibly smallpox. As the eldest son, Frank was expected to travel to Toronto to assist his father with opening and running a new restaurant. He remained living in Toronto for the rest of his life. Due to racist laws prohibiting people of Chinese heritage from entering Canada, Frank was not permitted to bring his wife Molly with him. She and children Ken and Susan finally joined Frank on December 31, 1948 when prohibitions against Chinese immigration were relaxed. Once the family was settled in Toronto, Molly had two more children, Linda and Bill. In 2004 Frank's children travelled to Fuheli Village where they were able to see for the first time the home their grandfather had worked so hard to build. |

Video: Interview In this clip Susan and Linda share the few details they know of their grandparent’s life as a young married couple. Marriage License and Passenger List This passenger list shows that Alice Grady sailed from Ireland to New York and was sponsored by her Uncle. She arrived on Oct. 24, 1906. See entry # 26. |

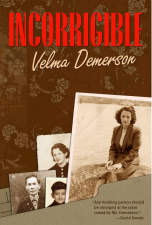

|

Velma Demerson I get in touch with Velma Demerson whose parents had her incarcerated because she was dating a man of Chinese heritage. She wrote about her experience in her 2004 autobiography Incorrigible. Demerson’s devastating account received a great deal of media coverage at the time it was published. |

|

Video: Interview With Velma Demerson In this clip Velma talks about how she came to meet Harry, her desire to remain a virgin, being raped in St. John, and her later intimate relationship with Harry. As you can see, Velma is at once very forthcoming, offering some of the most intimate and terrible details of her life, but she also gives very short answers. This conversation occurred at the beginning of our first interview. Over time, even over the course of this interview, she became much more relaxed and would offer longer answers. She also has a lovely and warm smile that you are more likely to see when chatting about more happy times. |

|

Click on photos to view slideshow. Chinatown Around The Time Velma Met Harry The 1921 Toronto City Directory is a useful tool for finding out where people lived and what businesses were in what neighbourhood. Looking at the listings on Elizabeth Street, notice that sometimes residents of Chinese heritage were listed simply as “Chinese,” whereas other people were listed by their names. Why do you think this might be? What else can we learn about this neighbourhood based on the Elizabeth Street listings?

|

|

Over the years Velma has amassed a small archive of documents related to her own life experience that she shared with me during our interview. Among the items was a tiny newspaper clipping about the annual meeting of the Presbyterian Women’s Missionary Society (PWMS). Missionaries worked overseas in China but they also worked among people of Chinese heritage in Canada. Their ultimate goal was to covert them to Christianity but their principle involvement in migrant’s lives was to provide a wide range of social and educational services. Most migrants who came to their churches did so to take advantage of English language classes. That the newspaper reported on their annual meeting shows how important women’s missionaries were at this time. The news story indicates that society members were concerned about the ostracism experienced by white women married to men of Chinese heritage. Because this sentence followed a sentence about northern Ontario where the mining industry attracted many male labourers and female sex workers I assumed that the problem they were referring to was in northern Ontario, not Toronto. Even so, if the PWMS investigated and reported on the matter it would shed more light on both these relationships and social attitudes toward them. I hired Anne Toews, a former Master’s student of mine who was doing her PhD at York University, to go to the Presbyterian Church Archives and investigate. She discovered that their work with white women was in Toronto, not northern Ontario. PWMS hired one of their members to help break these women’s social isolation. How is it that women living in the heart of a booming metropolis could be isolated? The PWMS records show that these partnerships were more common than even my narrators had guessed. I felt confident that the oral testimonies alone were sufficient evidence but finding written documents that corroborate narrators’ stories is always exciting, and made an even stronger case. This was particularly important since historians of people of Chinese heritage in Canada were certain that relationships with white women were extremely rare. It was going to take a lot to convince them otherwise. The documents Anne Toews found at the Presbyterian Church Archives would go a long way to help me in that endeavour.

Velma Gave Me This Newspaper Clipping The clipping tells me that the Presbyterian Women’s Missionary Society had an interest in relationships between white women and men of Chinese heritage. I hire Anne Toews, a former grad student now undertaking her PHD at York University in Toronto, to search the Presbyterian Church archives to find out more about their interest in the issue, and she strikes archival gold. |

|

Presentation Presenting your research findings at conferences is an important way to communicate with other experts and get feedback on your interpretations and arguments. I presented my findings at the 5th WCILCOS International Conference of Institutes and Libraries for Chinese Overseas Studies on Chinese through the Americas held May 16th to 19th, 2012 at the University of British Columbia. This was my first time attending and presenting at a conference about people of Asian heritage.

|

|

Video: Interview With J. Rosenthal J. Rosenthal talks about his mother Rose, the daughter of Jewish migrants who lived in Toronto's Ward district, and being raised by Chinese stepfathers. |

|

Click on photos to view slideshow. |

|

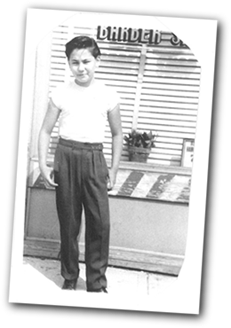

Video: Interview With Tony Chow Tony Chow discusses the race-segregated labour market.

Gordon Chong in front of Lew's Barbershop in Toronto. Video: Interview With Gordon Chong Gordon Chong describes the isolation and depression his white mother experienced as the wife of a man of Chinese heritage. |

|

Video: Interview With David Jean David Jean is of Chinese, African, and white descent and grew up in the Ward on the edge of Chinatown. He had close social relationships with the lesbians who hung out there. In this clip he paints a vivid picture of life in that neighbourhood. |

|

MethodWhen social scientists have a lot of data to examine we use a sampling method. One type of method involves randomly selecting documents from a large group. The method I chose was to examine all marriage certificates but only for select years. Anne searched certificates for the years 1921, 1924, 1927, and 1930. I chose the 1920s since marriage rates for Canadians declined during the Great Depression which lasted through much of the 1930s. It would be interesting to look at the 1940s. During the first five years of that decade there were fewer men of non-Asian heritage of marrying age around since they had enlisted in the war. Might this have led to an increase in marriage between non-Asian women and men of Chinese heritage?

Additional Resources: 1921 Census Anne Toews moved back home to British Columbia to begin writing her dissertation and recommended a replacement, Anne Cummings, to look at marriage certificates from the period. Cummings had done her MA at SFU with Anne, but I had not met her. I was excited to learn that marriage certificates contain a lot of valuable information about the marrying couple. The age, place of residence, declared employment, declared religion, and birth place was documented on the back of each license. This helps us get a sense of the class and heritage of the people involved. |

|

QuestionBack when I was a graduate student I would wander through the university library and randomly pick things up. I came upon what looked to be a rather dull government report. It was an analysis of the census data collected in 1921. What caught my eye was the complicated way the author of the report analysed the data on “racial origins.” I copied the report and have in the past used it in my teaching as a primary source for students to analyse. One mistake I found students made was to assume that in the 1920s, white Canadians were racist. Because of this preconception, they were not able to see that the author questioned the meaning of race. One of the most important historical skills is the ability to set aside any and all preconceptions. As you can see, the census data shows that in all of Canada there were 9 men of Chinese heritage married to non-Chinese women. How does this evidence square with the marriage certificates? Is the census a reliable source? What reasons might there be for the discrepancy between the story the marriage certificates tell and the story the census data tells? How might this affect the way you treat census data?

Additional Resources: 1921 Census Many years ago I happened upon this report and had used it as teaching material at McGill. I dug it out of my files -- finally! A use for it in my research.

|

|

The Toronto Star And Globe And Mail I had thoroughly reviewed the tabloids, but not the mainstream press. Doing this research was much easier because both papers have been digitized. Take note, however, that words searched are not always captured by a newspaper’s search engine. Old-fashioned indexes should also be consulted. For Canadian historians, an excellent resource is the Canadian Periodical Index. |

|

Why historians like murder, and, sometimes a lead takes you to dead endHistorians rely heavily on written records to develop an understanding of the past but for social historians who want to write about the lives of everyday people, finding records is more challenging. Most people never make it into the “official” record unless something quite extraordinary happens in their life. (It will be interesting to see how Facebook and other social media changes the stories historians can tell.) Murder cases are particularly valuable for the social historian for two reasons. First, they produce written evidence of those involved in the crime: the accused, the victim or victims, the families of both, and the general public whose reactions and opinions to the crime and trial are recorded by the news media. These documents often reveal something about the conditions in which people lived, worked, and played, and the social attitudes that prevailed. Second, when a murder involves people who are on the margins of society, journalistic coverage of public opinion about the murder produces a written record of the dominant group’s views. For example, if the perpetrator is diagnosed with a mental health problem, or is a member of an immigrant group, a broader discussion about what “society” – meaning the dominant white, able-bodied, “normal” group – should do about the mentally ill or immigrants will likely occur. If people get agitated enough, and if the political moment is right, reactions to the crime could lead to new laws that further restrict immigration or the lives of the mentally ill. In this way we can often learn a great deal about a society’s values and fears, and how they impact the law, politics, and the lives of those affected. We know a lot about public attitudes toward people of Chinese heritage in British Columbia because hostility toward them was so great that whites generated a substantial record of their attitudes in documents like the 1885 Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration and the news coverage of the 1907 “race riot”. There are fewer documents that record white Torontonian’s opinions about people of Asian heritage. All of my narrators who lived in British Columbia and later moved to Toronto claimed that Toronto was much less hostile toward them (see, for example, the Alice Yeh and Alan Joe’s interview clips), yet the tabloids expressed sentiments that were just as racist as those heard in British Columbia. If the death Go Wing Chow/George Quong/George Kwong* generated media coverage, it would shed light on social attitudes among whites in Toronto at the time, and help me corroborate – or challenge – Alice Yeh and Alan Joe’s testimony. On March 26th, 1927 Go/Quong/Kwong was found dead in his apartment on 243 Simcoe Street, the cause a knife wound to his chest. His wife, LePage, had been stabbed four times in the leg. In the course of the investigation it was suggested that LePage had another lover, Fred Low, who denied any involvement in the conflict. In the end Go/Quong/Kwong’s death was ruled a suicide. In its March 28th report on the case the Star described him as an “unfortunate foreigner,” suggesting a sympathetic rather than racist response to the incident. Add to this an even more tragic death: just four days later Tong Yong reportedly grabbed a knife from a butcher shop and ran into the street swinging. He killed 12-year old Elsie Moryarck by stabbing her in the back and was subsequently judged insane and institutionalized. The event was reported in the mainstream press but like the Go/Quong/Kwong-Lepage case it did not produce an outcry against Chinese immigration. This is all the more surprising since the two cases happened within a single week. The death of Go/Quong/Kwong did not produce any evidence about the dominant social group’s attitudes toward people of Chinese heritage, or did it? Does the fact that these two cases did not produce an outcry against Chinese immigration support Yeh’s claim about Toronto being less hostile toward the Chinese? Can historians make an argument about something on the basis of the absence of evidence? What do you think? Provide your answer in one or two well-reasoned paragraphs. *Names of migrants of Chinese heritage are complicated. First, in the west names are in reverse order: given name first and surname last. When people of Chinese heritage arrived in Canada, Canadian immigration officers treated the given name, which appears last, as the surname. Moreover, they wrote it down phonetically. This resulted in many different spellings of the person’s name, as we see in this case. The victim was identified as Go Wing Chow, George Quong and George Kwong. Many immigrants chose an English name for themselves, thus “George.” Sometimes people chose the same name as someone who had been kind or helpful to them, or who they admired, as was the case with two of the men I interviewed. At other times, Christian missionaries suggested names to them. Finally, when different officials took down information about these people -- at immigration entry points, for the purpose of the census, in news reports, and so on -- the writer wrote the name as they heard it. Quong/Kwong/Wong are just three ways one name might be transcribed into the official record. Can you imagine two or three challenges this creates for doing research on the history of migrants of Chinese heritage?

An Intriguing Story Was it murder or suicide? In the Toronto Star, we find the story of Margaret LePage and George Quong. Click the method/question to find out why historians like murder, and how sometimes a lead takes you to dead end. |

|

MURDER! Or Suicide? I have my research assistant Anne investigate further by looking at the annual constable reports to see if she can find out anything more about the case. The hunt for more info is a dead end.

These reports reveal information about people of Chinese heritage and the sex trade in Toronto. I have marked these sections with a red square. The full reports are available in the Archives section of this site. |

|

Secondary Sources This link takes you to my Zotero bibliography of sources for this project. Some of them I read many years ago, and some I read for the purpose of this project. Scholars usually have some familiarity with a subject before they begin research in a given area, but they also have to read new material to bring themselves up to speed with the most current literature. They might also want to engage with new theories and methods, which will also require more reading. |

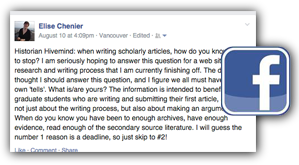

When to StopEven for established historians the best motivation for finishing a writing project is a deadline! When Nicolas Kenny sent out a “call for papers” for a special issue of Urban History Review, I submitted a proposal. It was accepted, so now I had a real deadline to work toward. This helped me establish firm writing goals. Recently I have adopted a number of tools to help me stay focused, and to prevent me from constantly checking email and social media feeds. I use SelfControl, an app that lets you block web sites of your choice (for me, email and Crackbook) for any amount of time you chose. I can still go online to look up books and articles and anything else related to my research needs, but I can’t get distracted by other online services. I also use the Pomodoro technique, which I find helps a lot. I don’t know why, it just does. Finally, I also listen to baroque music when I am working at my computer. Studies have shown that it helps with concentration and creativity.

How do you know when to stop researching? Your argument has to have enough evidence to support it, but how do you know you have enough evidence? Click on the Facebook image to see what other historians had to say. |

|

Call For Papers Editors of books and journals are constantly soliciting papers for publication. They send out a “call for papers,” which is an invitation to submit a proposal for an article. The editor then selects from the proposals a set of articles that fit best with their theme, and with each other. I know that if I submit a proposal to a call for papers and it is accepted, I will have a firm deadline to work to, and since a deadline is my best motivation to finish an article, I send in a proposal in response to a call for papers. |

|

Writing I complete the first draft of my submission. |

|

Editor's Feedback Comments from the editor. |

|

Mavis's Feedback Mavis read every version of my article and provided feedback. Initially the article was titled “Bachelors and China Dolls.” Bachelors refers to the men of Chinese heritage. They are known as “bachelors” in the historical literature because so few women of Chinese heritage came to Canada; most men were believed to be living without female companionship or sexual contact. I remembered having come across the term “China Dolls” back in the 1990s in one of the tabloids I read for my Masters research. Mavis challenged me on this term. She had never heard it, she said. I reviewed hundreds of articles to find the reference to China Dolls but had no luck. Instead I found a reference to “consent girls,” which I liked even more since it was an effort to distinguish those white women who freely and willingly chose to partner with men of Chinese heritage from those who were supposedly lured against their will into the arms of a “Chinamen.” “Consent girls” really captures the sexual politics of the era. |

|

What makes a scholarly journal scholarly is the fact that it is peer reviewed.What makes a scholarly journal scholarly is the fact that it is peer reviewed. What this means is that the journal’s editor sends copies of an article submission to two or three experts in the field and asks their opinion of the article. These reviewers do not check the facts. Although they may be familiar with some of them, they do not go to the primary sources the author used and check them for accuracy. Instead, they assess the argument and the analysis and interpretation of evidence. Because they are experts in the field, they may also identify gaps in the article, either in the primary or secondary source research. The reviewer assesses the article for its contribution to the existing scholarship. Does it make a new, innovative, interesting, and convincing argument? Is it well and clearly written? Does it fit with the journal’s mandate? The reviewer writes an assessment of the article and typically makes a recommendation to publish “as is”, publish with revisions, or, decline to publish. In my own case, revisions have always been requested, and I have almost always found the suggestions helpful and my article improved by them. Both the author and the reviewer remain anonymous to each other, although the reviewers may be able to identify you if you have given public talks about your research. Sometimes authors can make a pretty good guess at who the reviewer is, or might be, based on the comments they make. Historians tend to have certain key concerns that drive their scholarship, and if you are well read in the field, you know who is concerned with what issues. If those issues come up in the review, you can guess who wrote it. But, that is not the point! The point is, we remain anonymous so that assessments can be frank and objective, free from biases either for or against the author. Bias still exists, of course. A reviewer might have a negative opinion about the merit of the topic, or about the author’s methodology or critical framework. If a reviewer thinks oral history is an invalid source, the oral historian is sure to get a poor review. The editor of the journal, however, will usually attempt to find a reviewer whose research interests and methods align with those of the author. My first experience publishing in a scholarly journal taught me a very important lesson. I received three reviewer’s reports. The first one said the article was terrific and should be published as is, the second reviewer said the article was terrible and should not be published. A third reviewer thought the article was very good, but recommended specific revisions, which I made. This experience taught me that people read and value scholarship very differently, and a reviewer’s comments need to be taken with a grain of salt. The reviews for this article were, in my opinion, excellent. An excellent reviewer is one that “gets” what you are saying (or trying to say), that takes it seriously, that reads it closely, and offers feedback that will help you strengthen your argument, and ideally, encourages you to keep going. At this stage, it is very easy to be discouraged. Focus on the helpful reviews, and get ready to revise. To this day I still regret not revising an article that I really liked, but which was rejected from a top journal. I should have done the hard work of revising and re-submitting it to another journal, but instead I let my disappointment get in the way. Writing a review is an art. Receiving criticism is always tough, even for those of us who have been publishing for years. That’s why it’s so important to word your feedback carefully. Whether the journal decides to publish your article or not, good reviews should help you to write a better article. The two I received for this one most certainly did. The reviewers gave me permission to publish their reviews on this website. They chose to remain anonymous; permission was arranged through the journal’s editor. I have not been able to guess who they are!

Anonymous Reviewers What makes a scholarly journal scholarly is the fact that it is peer reviewed. What this means is that the journal’s editor sends copies of an article submission to two or three experts in the field and asks their opinion of the article. |

|

More Research Click on the link below to see a bibliography of the books and articles I read to address Reviewer B’s suggestion that I place my article more squarely within the literature on the history of emotion. After reading the article and having taken the suggestion very seriously, I felt compelled to re-write the entire article! That was not very practical since the deadline was looming. After consulting with Nicolas Kenny, the editor of this special issue, I chose to suggest ways that the evidence I had uncovered could be addressed from a history of emotion perspective. The editor found my changes acceptable and the revised article was handed off to the copy editor to prepare it for publication. Prompted by the reviewer’s suggestion to think more about the literature on the history of emotions, I read over one thousand pages of text. In the end, my revised and re-submitted article included only one and a half new paragraphs to address the critique. |

|

Revised Draft When an article is returned to you for revisions, you are given a strict deadline to meet. Getting your article in late means holding up the publication process for everyone involved. |

|

As the author, you do have a say in how the final article looks.Your article was accepted, your revisions are done, but it is still not over. Your article now will be copyedited. Language is political, therefore even the copyediting process can have its challenges. In this case I had two quibbles with the copyeditor’s changes to my article. As you may have noticed, I use “people of Chinese heritage” instead of ‘the Chinese’ or ‘Chinese Canadians.’ I recently read an article that sensitized me to how the identification of people by their race reproduces racialization. (If I could remember the article, I would cite it.) I expected the editor to change this somewhat clunky phrase to Chinese Canadian, but I was wrong. What the copyeditor did change, however, was the spelling of heteronormative to hetero-normative. I protested. There is a well-established field of sexuality studies that uses heteronormative without a hyphen. To hyphenate would be out of keeping with normal practice, and would make it appear as though I was not familiar with my own field of expertise. As you can see from the correspondence posted here, the copyeditor was following a grammatical rule, not the discipline’s practice. After calling the journal’s editor into the conversation, it was agreed to take the hyphen out. I also quibbled with the hyphen inserted between the compound adjective Chinese Canadian (a compound adjective is an adjective made up of two separate words). Grammatically, this is correct however the use of a hyphenated identity among Canadians of non-British descent has fallen out of favour. Although it was proper form to use the hyphen since it was a compound adjective, I did not want readers to think that I was using a term that is now regarded as a diminishment of one’s Canadian-ness. We don’t every say British-Canadian, for example. Presumably because the journal does not want to appear sloppy in it’s editing, they asked me to provide an explanatory footnote for the unconventional punctuation, which I gladly did. The lesson here is: don’t be afraid to engage in a conversation with copyeditors and editors. As the author, you do have a say in how the final article looks. Copy Editing Your article was accepted, your revisions are done, but it is still not over. Your article now will be copyedited. Language is political, therefore even the copyediting process can have its challenges. |

|

PUBLISHED! After 3 years of fascinating research and countless hours of writing, feedback and revisions my article is published. |

|

Feedback Thanks for using this site. If you want to share our website with your friends, please like us on Facebook, share our address on Twitter, or spread the news on Tumblr and Instagram. I would also be very glad to have your feedback. What did you like? What didn't you like? Are you a student, an instructor, or a curious web surfer? You can reach me by clicking here. |

LEGEND

![]() Questions that came upduring research

Questions that came upduring research

![]() Method and approach

Method and approach

![]() Clickable content

Clickable content